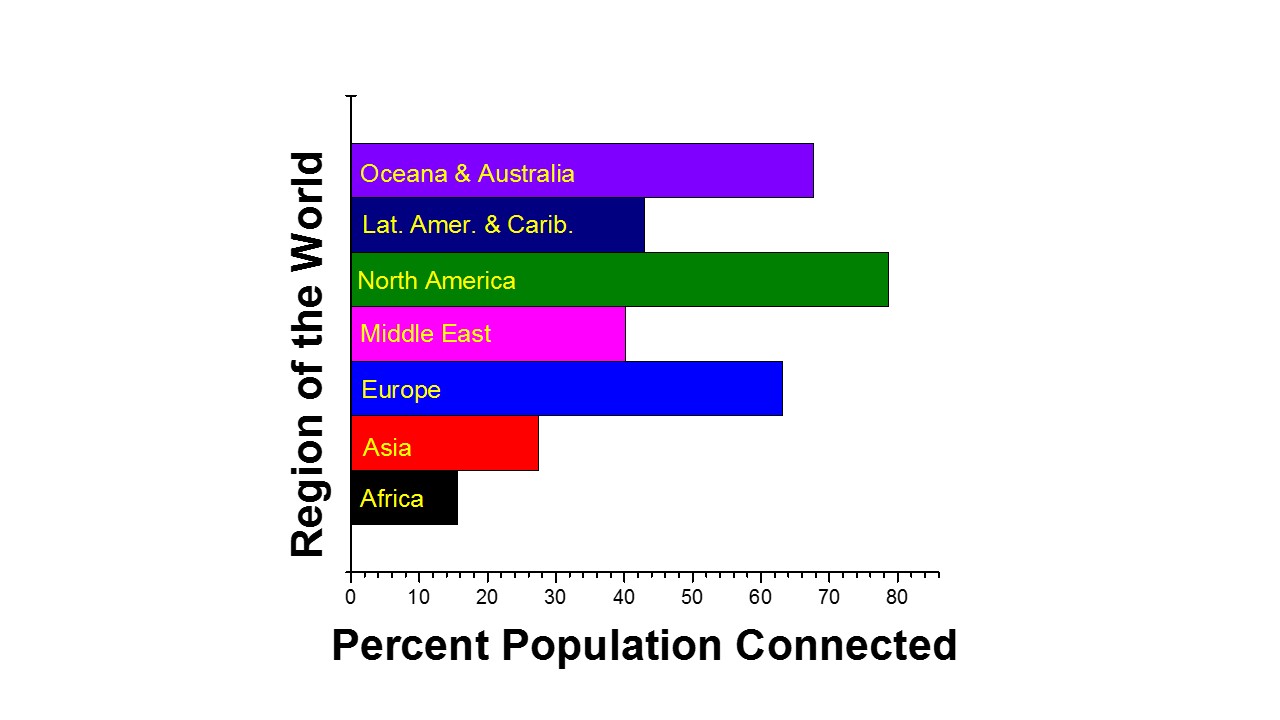

Figure 1 – A typical MTF Chart for a Canon Lens

During my recent trip to Vermont, I discovered that my ten year old Canon 18 – 55 mm zoom lens, the one that came with the original 300D Rebel had given up the ghost. If you try to get such a lens repaired its going to cost you about $150. In contrast if you buy a new one from a store like B&H Photovideo, it sells for about $199 and has the added advantage of being image stabilized. So no contest right? Well maybe not so much. I immediately started down the path of whether another lens would better serve my purposes, maybe a different moderate zoom range?

So setting $500 limit for myself, I entered the world of what lens to buy. You can start to read the customer reviews. This approach comes with the problem that these people don’t know what they are talking about, more often than not. So then you have to look at the technical specs of the lenses. There are a lot of parameters that define lens quality. But given my obsession for image sharpness a good starting point is the Mosulation Transfer Function or MTF.

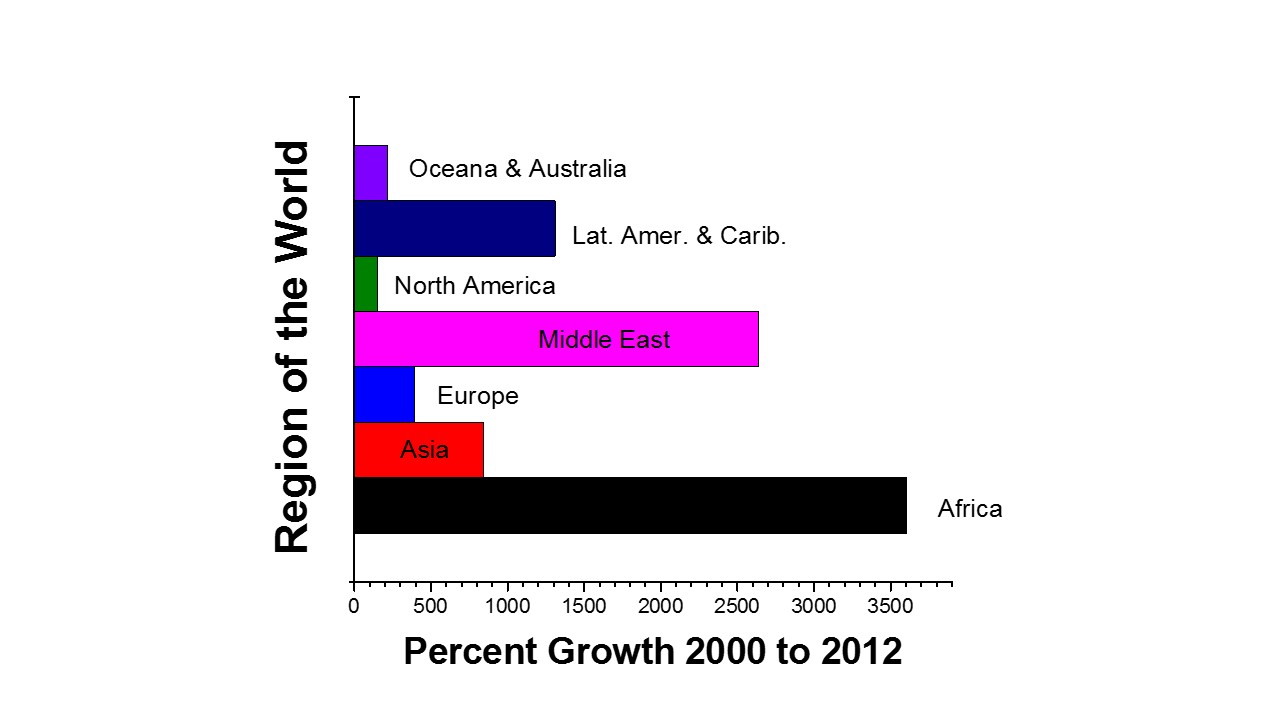

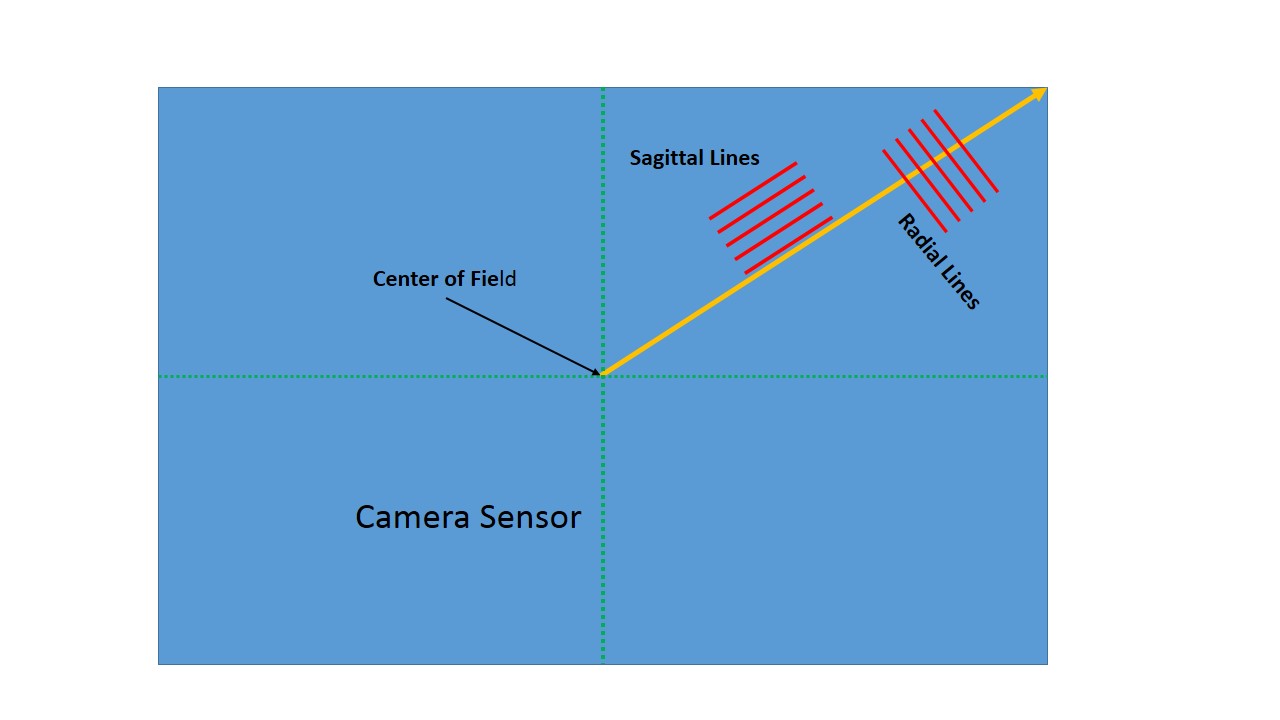

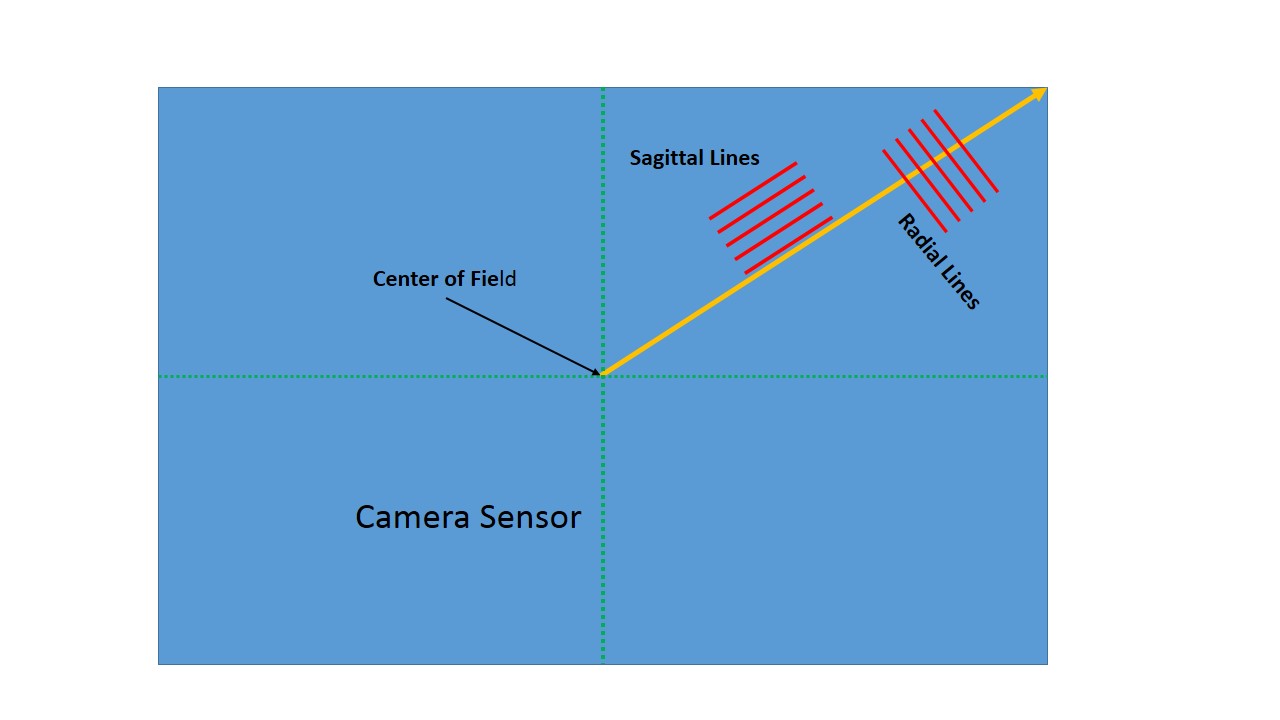

Figure 2 – Schematic defining terms in an MTF (c) DE Wolf 2013

In today’s blog I’d like to talk technical about how to read an MTF curve and then, in my next technical blog, I’ll discuss the choice that I made and how I made it. We have previously discussed resolution in terms of how a lens handles a set of parallel line or line pairs. Simply put if you have a set of white lines and black lines, where the line thickness equals the line spacing, and unless the lines are very wide and far apart the lens is going to distort the lines. It does this in two ways: it smooths or unsharpens the line edges and it modulates the lines. Huh? Modulates mean that black becomes gray and white becomes gray until when the line spacing is so fine you can no longer distinguish the two shades of gray. Suppose black is 0 and white is 255, then a 10 % demodulation takes the contrast down to 90 % of what it was to begin with. The difference between black and white is now only 230. That’s what the MTF does. It tells you how much the lens( or lens/camera system) modulates the contrast, expressed as a fraction, where 1.00 or 100% is maximum.

Figure 1 shows a typical MTF Chart from Canon. Obviously, it requires a bit of explanation. First, you will recall that the sensor on a digital camera is typically rectangular. For a full frame 35 mm camera this rectangle is 25 mm X 36 mm. The corner to corner diagonal distance is approximately 44 mm; so the center to corner distance is approximately 22 mm. In Figure 2 the blue rectangle is mean to be the camera sensor. The arrow goes from the center to the corner; so it is 22 mm long. The x axis of Figure 2 is meant to be distance from the center along this arrow. Next imagine that we had a set of lines parallel to the radius (referred to as meridional lines), and at each point along the radius we measured the modulation of these lines. We can refer to this as the meridional modulation transfer function. The key point is that the camera’s ability to resolve lines falls off from the center of the sensor to the edges; so the MTF decreases.

If you think about it, you will realize that the lines could alternatively be parallel to the radius instead of perpendicular to it. So you could alternatively measure the MTF for parallel lines. Parallel lines are referred to as sagittal lines. I’ve always liked the word sagittal. Sagittal comes from the Latin word sagittalis, meaning arrow. You may be familiar with the constellation, or Zodiac sign, Sagittarius, the archer. So the MTF measured with lines parallel to the arrow is referred to as the sagittal MTF. This gets a bit confusing and you might ask why the resolution of the two types would different. With a perfect lens they would be the same. However, if they are different the lens is said to have astigmatism. So comparison between the two MTFs is a good measures of the lens astigmatism.

So here’s how it all works. The two MTFs are usually measured at two line spacings, 10 line pairs/mm and 30 line pairs/mm. 10 lp/mm is meant to be a measure of the lens response to low spatial frequencies and the 30 lp/mm to high spatial frequencies. That would give you four curves. However, it is usually measured both with the lens wide open and with an f-number of 8.0 (near the sweet spot for lens resolution); so worst and best resolution. This is why there are eight curves in Figure 1. So here we go. The thick lines are measurements taken at 10 LP/mm and the thin lines are at 30 LP/mm. The black lines are measurements taken with the lens wide open, and the blue lines are with the lens at f/8. The solid lines are meridonial measurements while the dotted show the sagittal measurements.

Now the key point, a value of 0.8 or greater represents superior lens performance. A value of 0.6 represents only satisfactory performance. So you know what you’re looking for 0.8 or better everywhere and at a cheap price. Finally, one saving grace if you are using a Canon camera with an APS-C sensor with dimensions 14.8mm x 22.2mm. Then the radius is only about 13 mm, so you only have to worry about lens performance out to 13 mm.

As I said at the outset, totally defining lens specifications is a complex issue. But the MTF is represents a good starting point and at least gives you a peg on which to hang your comparative performance. Do remember caveat emptor that individual lenses can vary and a lemon is sour no matter how you slice it. So you’ve ultimately got to field test your lenses, while you can still return them.

I will return to the question of which lens I bought and why in my next technical blog. Wait a minute, David. Aren’t you going to tell us where to find the MTF data. For Canon lenses go to the Canon DSLR site and click on the picture of your lens. The MTF’s are on the bottom of the page. The situation with Nikon lenses is similar. Go the the Nikon Lens Site, click on the lens you’re interested in and you’ll then see a link to the MTF Chart.