Figure 1 – Pierre and Marie Curie in their laboratory c 1904 from the Wkipedia and in the public domain by virtue of its age. Photographer unknown.

Let’s face it, demagogues and rock stars are generally more popular than scientists. Still it may be argued that the legacy of the scientist is ultimately more enduring. I started thinking the other day about historic photographs of great scientists, and the point struck me that such images are often very contrived in the sense that they are often constructed so as to show the scientist in his/her natural habitat, as it were. There is so often a symbol of their discovery in the photograph. They are memetic, and probably their endurance derives from the timelessness of the meme. More fundamentally, these images are so often advertisements. We always hear about how the scientist is ever seeking money to fund discovery; so often the image was taken for fundraising purposes.

I think that a very key example of this are images of Madame Curie. She was always seeking money to fund research or charities, and her story, her trials and tribulations, are legendary. Figure 1 is a classic image of the Curies in their laboratory. Pierre is gentlemanly and gaunt. He looks at us and seems to stand in deference to his wife. Marie is beautiful in simplicity. And the instruments, we love looking at them. Principal here is the balance. But there are others, and Pierre was famous for his self-built instruments, often the finest in the world.

Let me pause for a moment. The Curies were truly heroic figures, and it is not because of the difficult conditions that they worked under, nor because of Pierre’s untimely death by horse carriage. It is because every chemist of the day knew the fundamental mantra of chemistry, that matter could not be created or destroyed; it could only change its form. The transmutation of elements, turning lead into gold, was misguided superstition. But then their research led them down the forbidden path. They checked their calculations and then heroically followed that path. I cannot overstate the point. These were Olympian figures that created a new age.

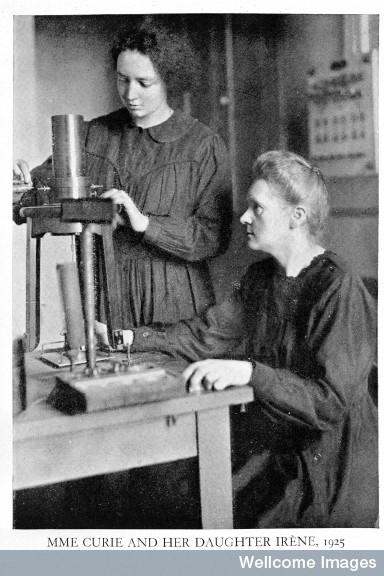

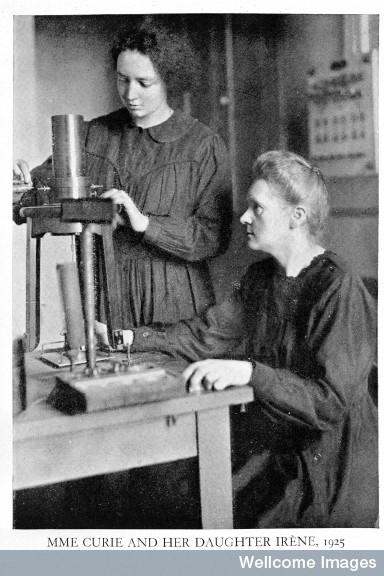

L0001759 Portrait of Marie Curie and her daughter Irene

Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images

images@wellcome.ac.uk

http://wellcomeimages.org

Photograph: portrait of Marie Curie and her daughter, Irene; anon., 1925.

Photograph

1925 Published: –

Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

But the public image of Madame Curie was more complex. Yes, she was a great scientist. In 1903, she was the first woman to win the Nobel Prize in Physics. Significantly only after Pierre’s protestations that she be included. In 1911 she won it for a second time in Chemistry.

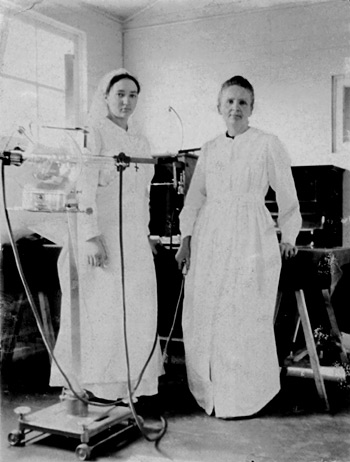

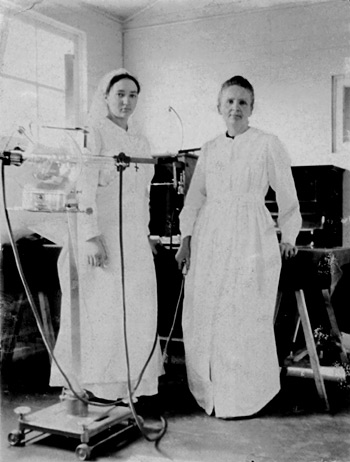

There were so many images that emphasized her feminine side – motherly portraits with her children. My favorite is Figure 2 from 1925 that shows Marie working in the laboratory with her daughter Irene, who ultimately also won the Nobel Prize. The image that completes this developed public persona is that of Figure 3, which shows Madame Curie with a nurse and her portable X-Ray machine to help French soldiers on the Western Front during World War I.

Figure 3 – Marie Curie with a nurse and her mobile Xray machine during World War II. From the Wikimedia Commons and in the public domain in the US because of its age.

Marie Curie was on of the great scientist of and for all time. She stands as a defining figure of the twentieth century. Her own words about being a scientist were simple:

“A scientist in his laboratory is not a mere technician: he is also a child confronting natural phenomena that impress him as though they were fairy tales.”

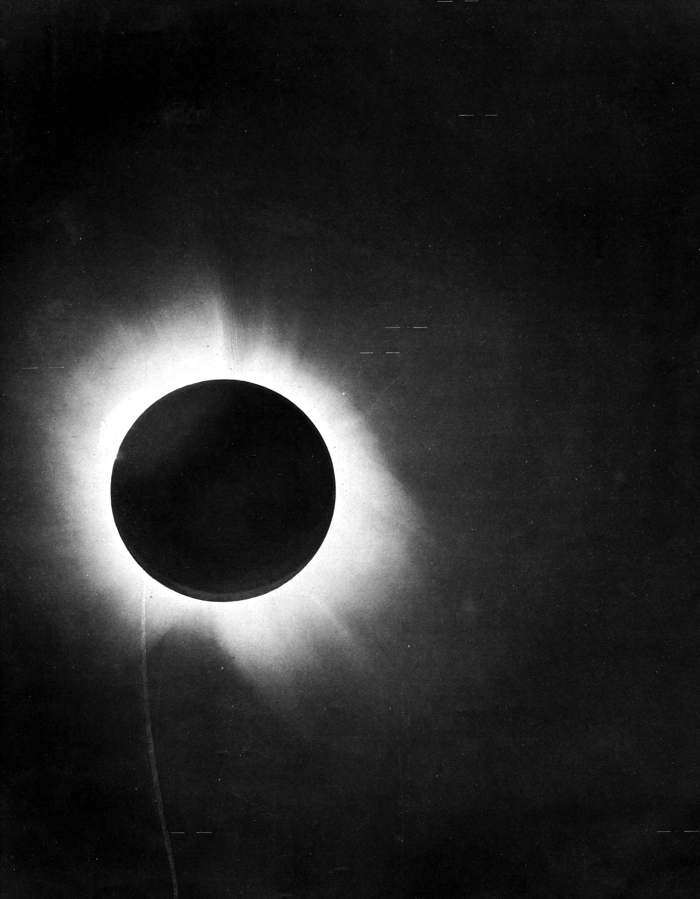

But let me not end with a quote. I’d like to share one more photograph – something very different that seems so meaningful. Figure 5 shows Madame Curie and Albert Einstein together deep in conversation. The image, like the world it alludes to, is foggy, grainy, and dark. It is cold and not yet known. It must be confronted and the cobwebs of fairy tales cast aside.

Figure 5 – Albert Einstein and Marie Curie from the Wikimedia Commons and in the public domain in the US because because its copyright has expired and its author is anonymous.