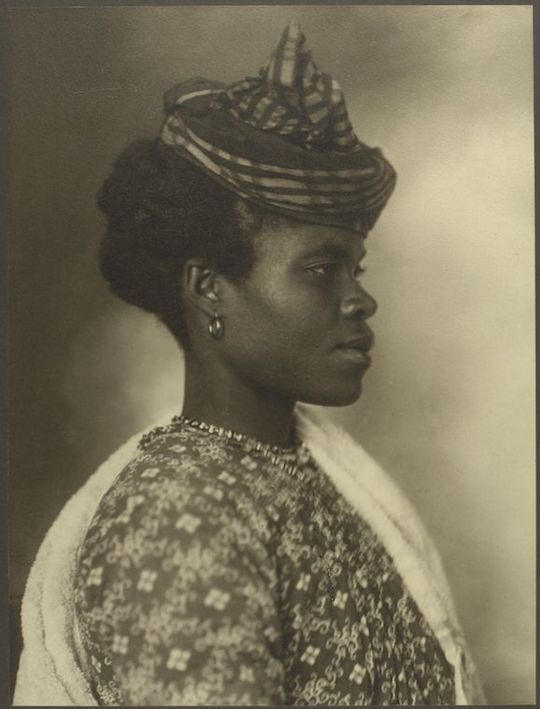

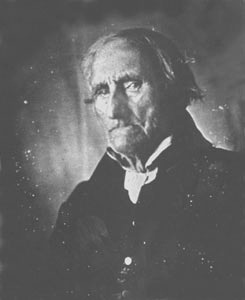

Figure 1 – Margaret Neves (1792-1903). In the public domain in the United States because of its age.

In his landmark, and I think very profound, book “Darwin’s Dangerous Idea,” Daniel Dennett tells us of a coin toss contest. The premise is this, suppose I were to tell you that I can show you a person who has one 100 coin tosses in a row. You would probably say: “No way!” But point of fact, it can be done with 100 % certainty. All you need to do is get 2100 people pair them off randomly. Take the winners, pair them off randomly, and continue the process one hundred times. Now a few points, first, that’s 1,267,650,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 people, which is not only a lot but a lot more than the number of people living on the Earth. But hey, this is science fiction. Right? Or at the very least it is a Gedanken Experiment. But the point is that while the winner was/is/will be chosen totally by the laws of random chance, and who said that God does not roll dice with the universe, he/she is certain to feel specially endowed by the Creator.

A similar logic applied to the three remaining members of the club, or is it tontine, of people alive today who were born in the nineteenth century, which was the subject of Tuesday’s blog. Actually, it’s not the same thing, because people who live long tend to have family members who also live longer. So genetics does play a factor. Anyway, Tuesday’s blog got me wondering about the eighteenth century. Who was the last person born in the eighteenth century to live into the twentieth century? I know, I know, who really cares? But bear with me. The interest in that question is that photography was invented in 1838, so the person in question, the winner of the coin toss as it were, was most likely to have been photographed.

The problem with all of this is that record keeping in the eighteenth century was not what it was in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. As a result, you wind up with an answer to the question of who was best documented to have accomplished the feat, not necessarily who actually lasted the longest. Anyway, a lot of people’s money is on Margaret Ann Neve (18 May 1792 – 4 April 1903) of St. Peter Port, Guernsey, English Channel, who is shown in Figure 1. She was the first documented woman supercentenarian, that’s someone who lives to be older than 110.

We know very little about her. She remembered the turmoil brought to Guernsey by the French Revolution. She married John Neve in England in 1823 but returned to Guernsey in 1849 after his death. Thus, she survived him by 54 years. Neve frequently traveled with her sister with her sister, who lived to be 98. Note that her mother lived to be 99. Their last trip was to Crakow on 1872. travelled abroad to various countries with her sister, who died aged 98. Their last trip was in 1872, when they visited Cracow (then in Austria-Hungary, now in Poland). Margaret Neve died peacefully on 4 April 1903 at age 110 years 321 days. At the time she was believed to be the oldest living person.

As I said, it is really hard to tell whether Ms. Neve

Before leaving this subject there is another question to consider and that is “Of all the people who have ever been photographed, who had the earliest birthday.” Photography was invented in 1838; so again the person had to have been born in the eighteenth century. Hmm! A while back I posted a blog about an 1842 photograph of Mozarts wife Constanza (1762 – 1842). Probably not, right? Because she was a mere 80 years old at the time.

As it turns out, the answer relates to something else that we spoke about “The Last Muster Project” and book by a similar name, by photo-detective Maureen Taylor. In 1864 the Rev. Elias Brewster Hillard a congregationalist minister from Connecticut set out desperately to document these “Last Men,” the last surviving veterans of the American Revolutionary War before they died out. He published his photographs and stories in “The Last Men of the Revolution (1864).” The date is important, because at the time the nation was embroiled in a civil war that put at jeopardy what these men set out to accomplish.. Indeed, I would argue that the American Civil War as a fight for liberty was the American Revolution, part II. This book was reprinted by Barre Publishers in 1968. Hillard recognized the importance of this task of preservation. Ms. Taylor, using modern techniques set out with her Last Muster Project to discover more of these memorable men and women. Her book documents the lives of seventy of these individuals.

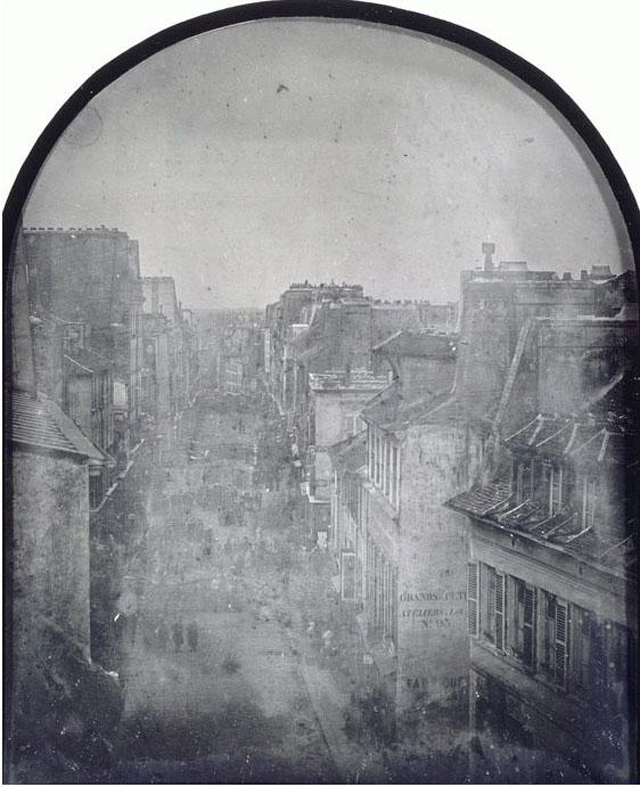

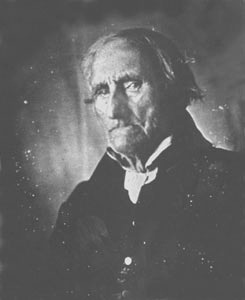

So who mustered last. Figure 2 is from a daguerreotype in the Collection of the Maine Historical Society that was taken c1852 and shows Conrad Hayer (1749-1856), sometimes spelled Heyer. Hayer was born in 1849 and the photograph was taken in 1852. It seems likely that he was the person with the earliest birthday ever photographed alive. I put the alive part in there so that people don’t through King Tut and the like at me.

In the end we cannot really be sure of either Neve’s or Hayer’s claims to photographic history. Indeed, I hope that readers can find and inform us of earlier people.

Conrad Hayer (1852) probably the person with the earliest birthday ever photograhed. In the Maine Historical Society and in the public domain because of its age.