Figure 1 Woman and Christmas tree c. 1860. in the Public Domain in the United States because of its age.

Yesterday was our first snow of the year, and this morning it is absolutely gorgeous! I have been trying to get into the “Christmas Spirit” by ignoring world and national events and by searching the web for antique Christmas images. What I have found is an amazing consistency of western tradition. Christmas is pretty much the same as it has always been. There are styles and regionalisms, of course, but the fundamental celebration remains the same.

“One Christmas was so much like another, in those years around the sea-town corner now and out of all sound except the distant speaking of the voices I sometimes hear a moment before sleep, that I can never remember whether it snowed for six days and six nights when I was twelve or whether it snowed for twelve days and twelve nights when I was six.”

Dylan Thomas, A Child’s Christmas in Wales

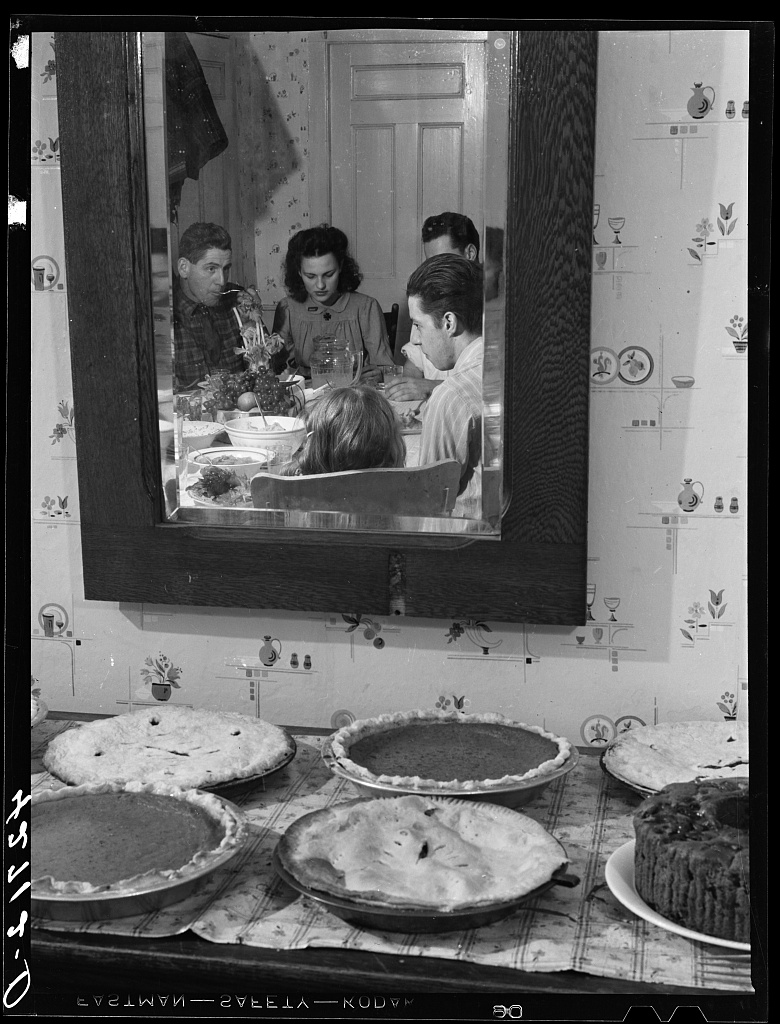

There are literally thousands of images, both candid and posed, of excited children and families in their “Sunday Best” posed rigidly in front of Christmas trees. These span the period from the 1860’s to today. I am particularly delighted by a photograph of “mom” from 1959 happily holding her cherished gift of Ricky Nelson albums.

Figure 1 shows a young woman in crinoline from around 1860 standing before “the family” Christmas tree. We feel that we could inject ourselves, or be injected, seamlessly into this little happy scene. I find myself wanting to extend my perception, to look out the window and wonder what is going on in homes next door.

“Quite deliberately my friend drops a kettle on the floor. I tap-dance in front of closed doors. One by one the household emerges, looking as though they’d like to kill us both; but it’s Christmas, so they can’t.”

Truman Capote, A Christmas Memory

We connect with frozen memories, contrived or real, from Christmases past. And we are compelled to add to the mountains of photographic memories. So many will be posted on Instagram and Facebook this December 25. Let’s take a lesson from Old Scrooge and remember how to laugh.

“Really, for a man who had been out of practice for so many years it was a splendid laugh!”

Charles Dickens, A Christmas Carol