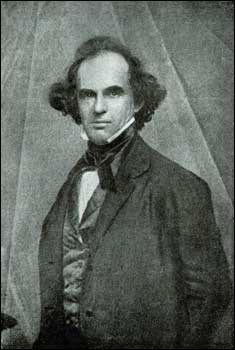

Figure 1 -Daguerreotype of Nathaniel Hawthorne by John Adams Whipple, Boston. (Peabody Essex Museum) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

It all makes one wonder how the people of the daguerreotype era themselves viewed these images in amalgam. An excellent hint is given by Nathaniel Hawthorne’s contemporary account in his story “The House of Seven Gables,” which by the way still stands and is a gorgeous museum to the author in Salem, MA. Daguerreotypes feature strong in this story.

“If you would permit me,” said the artist, looking at Phoebe, “I should like to try whether the daguerreotype can bring out disagreeable traits on a perfectly amiable face. But there certainly is truth in what you have said. Most of my likenesses do look unamiable; but the very sufficient reason, I fancy, is because the originals are so. There is a wonderful insight in Heaven’s broad and simple sunshine. While we give it credit only for depicting the merest surface, it actually brings out the secret character with a truth that no painter would ever venture upon, even could he detect it. There is, at least, no flattery in my humble line of art. Now, here is a likeness which I have taken over and over again, and still with no better result. Yet the original wears, to common eyes, a very different expression. It would gratify me to have your judgment on this character.”

There is the magic of photography again. You can hide the darker regions of your soul and disposition behind a disingenuous small. But the photograph, the daguerreotype penetrates. It reveals your true character. Like Anubis it weighs the value of your heart.