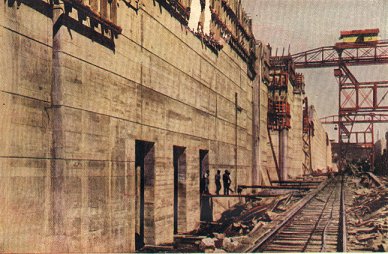

Figure 1 – The Pedro Miguel Locks of the Panama Canal photographed by Earle Harrison in color using the Autochrome Process. From the Wikimedia Commons uploaded by Mschlindwein and in the public domain because its was photographed before 1923.

In addition to the centenary of the start of the First World War, this August, August 15th to be precise, marked the opening of the Panama Canal, that great dream of a “Path Between the Seas.” I have been looking at a lot of photographs of the construction of the canal, including, of course, many pictures of that larger than life and somewhat controversial figure, President Theodore Roosevelt.

Most interesting among them are the color autochromes of Earle Harrison. Figure 1 is an example of these and you might also what to check out the link above for some more dramatic examples. The whole collection of these images was recently reissued.

I have spoken at length about the autochrome process and will, in fact, admit to be really intrigued by it. The Autochrome process works as follows. An adhesive layer was coated onto a glass plate. Potato starch grains graded to 5 to 10 um where attached to this layer. The starch grains were dyed with either red orange, green, or blue violet dye (an unusual color wheel). Gaps between the grains were filled with lamp black (essentially soot). This fragile layer was coated with a shellac and then overlain with a conventional silver halide gelatin emulsion. Because of the high sensitivity of these emulsion to UV light from the sun, a yellow orange filter needed to be placed in front of the camera lens when taking a photograph to block-out these rays.

When a photograph was taken the colored potato starch grains acted as minute filters. The silver halide emulsion was developed by conventional means and then reversed to a positive by what is effectively a bleaching process. Since the colored starch matrix remains intact, when the positive image (say illuminated from behind) will become colored as light passes back through the filter matrix.

Like our own time, the early twentieth century was a period of huge technological advancement, posing a series of complex moral an ethical issues. Indeed, it is all really an accelerating continuum. And again like our own time, it was a period of great ethical hypocrisy. World War I represented the worst that technology had to offer, highly efficient mechanized killing. The Panama Canal represented the middle ground. There was the dream, powered by visions of huge profit, that drove men to build the canal, which was the ultimate Herculean project. It took over thirty years to complete, and was a triumph (?) over nature both in terms of the actual digging and reinforcement and in terms of overcoming yellow fever. The autochrome, I would argue, ever subtle, was the best.

Humans see in color, and as long as photography was confined to black and white there was something important missing. Color represents a significant dimension of reality. Actually, as we have seen it really adds three dimensions. And thanks to the Lumiere brothers we can look back and marvel, as if we were there for the events. Shackleton set sail for his destiny in the Antarctic. The Panama Canal opened. And Europe leaped head first into disaster. All caught on camera.

Pingback: Theodore Roosevelt in Color | Hati and Skoll Gallery