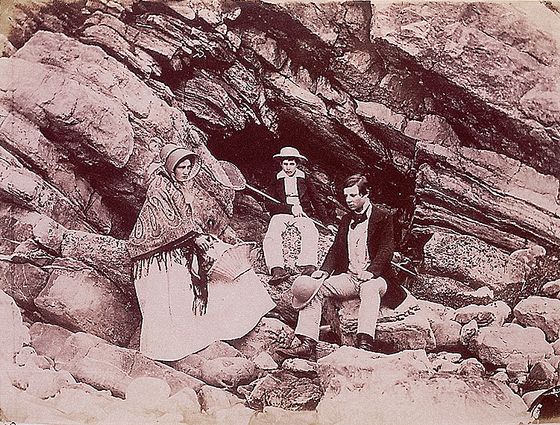

Figure 1 – John Dillwyn Llewelyn, Theresa, John, and Willie at Caswell, 1853, from the Wikimedia Copmmons and in the public domain.

Last week I was reading about a man in Wales, who was cleaning out his garage in 1973 and came upon a box of old daguerreotypes. His brother-in-law sought the advice of Noel Chanan, a photographer and filmmaker. The rest, as they say, is history. The box contained upwards of forty family images by the great-great grandfather of the man, John Dillwyn Llewelyn (1810-1882). Llewelyn was a British amateur scientist and photographer. He was married to a cousin of Henry Fox Talbot.

Llewelyn’s earliest attempts at photography were not, in his opinion, all that successful. He experimented both with Talbot’s process and with daugerreotypes. After a few years he abandoned photography, but picked it up again in the 1850′ s by which time the processes had advanced considerably. He invented what he called the “oxymel process,” which combined honey and vinegar to produce a dry plate. This was important because the wet colloidal process, then in use, was cumbersome in that it required the photographer to immediately develop his/her negatives. With the “oxymel process” the glass negative could be held for a few days before developing. He is also credited with the invention of an instantaneous shutter – enabling for instance the photgraphs of breaking waves and moving water.

Many of Llewellyn’s photographs can be seen on Noel Chanan’s website. He has also recently released a biography of John Dillwyn Llewelyn, “The Photographer of Penllergare,” which is available through the website.

Figure 1 is an excellent example of Llewellyn’s work. It shows his family (Theresa, John, and Willie at Caswell in 1853). This is precisely the kind of intimate glimpse of nineteenth century life that we have been talking about. There is a sharp freshness to the scene, and we almost imagine that we are there with them. They do not stare back at us, but rather appear to be involved with each other. They seem however, as I have suggested before, not oblivious to us, but rather seem to know that we are out there (here).

Both the book and Mr. Chanan’s website are filled with this kind of familial image. But there are other outstanding gems as well. I particularly like “The Stag, 1856,” which appeals to a sense of English mythology and was taken using a taxidermy specimen because a real stag could not be counted upon to stand still long enough for proper composition and exposure. I also think that “St. Catherine’s Island, Tenby, 1854″ is as fine a piece of landscape photography as I have ever seen. As is always the case we can learn a lot from these early photographic pioneers. Their compositions a classical sense of what a picture should be.