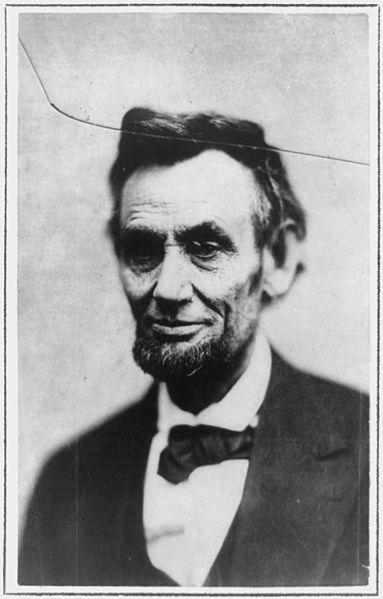

Figure 1 – Alexander Gardner’s February 5, 1865 photographic portrait of Abraham Lincoln. Image from the Wikimedia Commons and in the public domain.

The Opinionator Section of the New York Times has been carrying an intriguing four part commentary by Errol Morris on Lincoln and photography, “The Interminable, Everlasting Lincolns.” I was particularly struck by part three because it resonates with what we have talking about in regard to nineteenth century photographs. Indeed, I think that it takes the subject a step further in recognizing the special quality of “the photograph” to reveal the human soul in a way that painting never will. I know that’s a very strong statement. But the point is that an artist can draw what (s)he wants, a photographer captures – and then Photoshops. The last part is cynical David talking.

Morris relates a wonderful story. It seems that in 1909 Count S. Stackelberg visited the estate of Leo Tolstory, Yasnaya Polyana, to try to convince him to write a piece about Abraham Lincoln for The New York World. This was presumably for the centennial of Lincoln’s birth that year. (As an aside Lincoln was born on the same day as Charles Darwin – two men destined to change the world in very different ways). Tolstoy turned down the request but in doing so related a story to Stackelberg.

It seems that years before he (Tolstoy) had been traveling in the Caucasus and became the guest of a Caucasian Chief of the Circassians. It seems the Chief wanted to hear stories of the great leaders and generals of the western world. So Tolstoy, who just happened to be one of the world’s greatest story tellers, told him of the Czar, of Napoleon, and of Frederick the Great. But it seems the Circassian Chief was dissatisfied. Something was missing. Count Tolstoy had failed to tell him of the greatest leader of all, a man called Lincoln.

So Tolstoy told the Chief all that he knew about Lincoln. But still the Chief wasn’t satisfied. Despite the Count’s great skills at story telling, he had failed to truly flesh out Lincoln. The Chief wanted to see a photograph. And so Tolstoy arranged for this to happen – remember late 19th century, you just don’t look that sort of thing up on your IPad. Still Count Tolstoy knew someone in the next village whom he thought might have such a picture. And now let me let Tolstoy tell the story in his own words (via Morris’ article):

“One of the riders agreed to accompany me to the town and get the promised picture, which I was now bound to secure at any price. I was successful in getting a large photograph from my friend, and I handed it to the man with my greetings to his associates. It was interesting to witness the gravity of his face and the trembling of his hands when he received my present. He gazed for several minutes silently, like one in a reverent prayer; his eyes filled with tears. He was deeply touched and I asked him why he became so sad. After pondering my question for a few moments he replied: ‘I am sad because I feel sorry that he had to die by the hand of a villain. Don’t you find, judging from his picture, that his eyes are full of tears and that his lips are sad with a secret sorrow?’”

Morris likes to imagine (hope) that the picture shown to the Chief was the so-called broken glass photograph that was one of the very last photographs of Abraham Lincoln. And you can read more about this is Mr. Morris’ series. It was taken at the studio of Alexander Gardner (1821-1882) on February 5,1865. It is often referred to as the last photograph of Lincoln – and may, in fact, be. The story of Lincoln’s life, his trials and tribulations, his sorrows are indeed written on his face and contained in his eyes. Both Tolstoy’s story and Gardner’s photograph, are in a very real sense, truly privileges to hear and see. They bring us back more than a century and they admit us to the private recesses of a man’s soul. We are enriched by them, and such is the magic of photography.