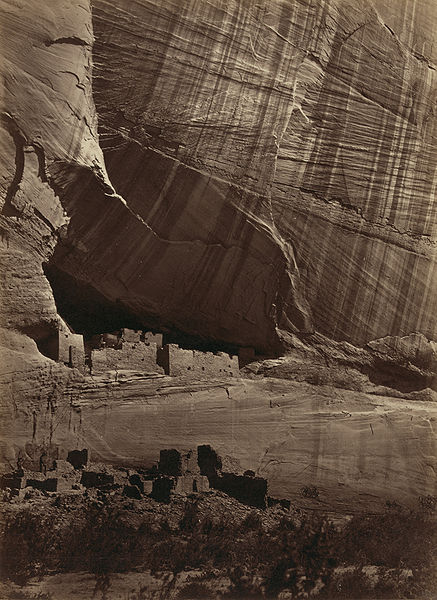

Figure 1 – Timothy H. O’Sullivan, Anasazi Ruins, 1873, from the Wikimedia Commons and the LOC in the public domain.

During the past week, I have spoken of nineteenth century American photographer Timothy O’Sullivan (1840-1882) twice, first in the context of his most famous and iconic images of the aftermath of the Battle of Gettysburg and second yesterday regarding his flashlamp images of Nevada miners.

O’Sullivan came to America from Ireland in 1842, While still in his teens, he worked for Mathew Brady. In 1861 at the outbreak of the American Civil War, O’Sullivan was commissioned as a first lieutenant in the Union Army. He appears to have principally been a surveyor for the army and he took photographs on the side.

In 1862 O’Sullivan was discharged from the army and was again employed by Brady, this time to follow the campaign of Maj. Gen. John Pope in Northern Virginia. He subsequently left Brady going to work for Alexander Gardner. This lead to publication of forty-four of his photographs in “Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the War,” including his most famous photograph of dead soldiers at Gettysburg. After Gettysburg, O’Sullivan documented Ulysses S. Grant’s siege of Petersburg and also photographed Robert E. Lee’s surrender at the Appomattox Court House in April 1865.

After the war and from 1867 to 1869, he was official photographer on the United States Geological Exploration of the Fortieth Parallel under Clarence King. We have already discussed his flashlamp images documenting miner on the Constock Lode in Virginia City, Nevada. The goal of this work was to attract settlers to the American West and what O’Sullivan did was to document the rugged and beautiful American west. The term “geophotography” has been used to describe this genre of photography.

I have heard it criticized as being of a purely documentary nature. I believe this to be very far from the truth. These photographs bear both technical and artistic proficiency. They also speak to the wonder of human eyes when first confronted by awe inspiring nature. Significantly, O’Sullivan was also the first to document and record ancient American ruins, revealing that the white eyes of the nineteenth century were not really the first to occupy these spaces. That was an important lesson, one that ultimately defines America.

In 1870 O’Sullivan joined a survey team in Panama to explore the possibility of cutting a canal across the isthmus. Then from 1871 to 1874 he joined joined George M. Wheeler’s survey west of the 100th meridian west. O’Sullivan spent his final years in Washington, DC where he was the official photographer for the U.S. Geological Survey and the Treasury Department. He died very prematurely of tuberculosis in 1882 at the age of forty-two. We can, however, say that his legacy lives on in the work of generations of American photographers, like Ansel Adams, who followed in his footsteps and photographed the natural beauty of the American West. This work still spell binds us and defines the American psyche.